Blog

Literacy By Any Means Necessary: The History of Anti-Literacy Laws in the U.S

Share

(This piece was originally published and updated on www.carliandcompany.org on December 2021. We are sharing an excerpt, for full article please visit www.carliandcompany.org/blog)

Written by Carliss Maddox

January 12, 2022

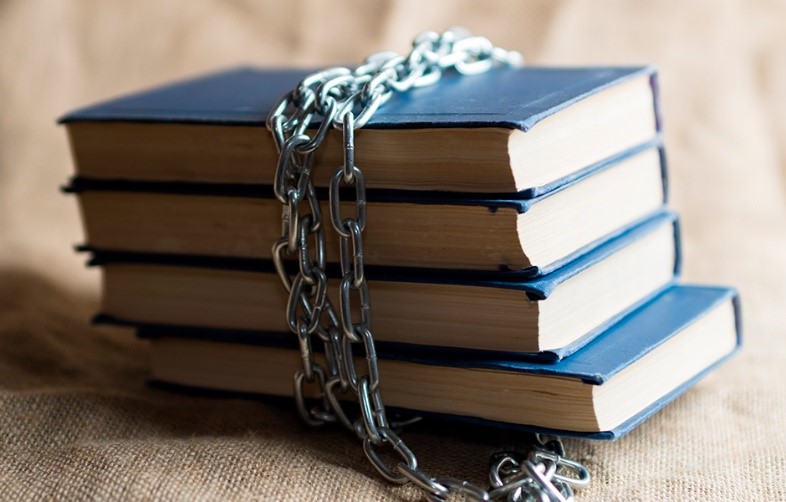

Imagine being one of those readers seeking knowledge that reflects on your own human experience and being withheld from doing so. Unfortunately, in the United States, there was a time when certain individuals were prohibited from learning to read or write based on the color of their skin. Historically, black people were not allowed to read, write, or even own a book because of anti-literacy laws. Anti-literacy laws made it illegal for enslaved and free people of color to read or write. Southern slave states enacted anti-literacy laws between 1740 and 1834, prohibiting anyone from teaching enslaved and free people of color to read or write. The purpose of this blog is to shed light on the history of anti-literacy laws that restricted black people’s access to literacy and to demonstrate the resilience of a people who used their emancipated minds to obtain literacy by any means necessary.

Anti-Literacy Laws and Abolitionist Frederick Douglass

Confederate states in the antebellum South that passed anti-literacy laws included South Carolina, North Carolina, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Virginia, and Alabama. Due to fear following the Stono Rebellion, the largest slave uprising in South Carolina in 1739, blacks were prohibited from learning to read. Plantation owners feared that literate slaves could write and use forged documents to gain their freedom. However, many of the enslaved used this method to obtain their freedom. Slave owner Hugh Auld describes this fear in this exchange with his wife, Sophia Auld, after he discovered her teaching a young Frederick Douglass how to read:

He should know nothing but the will of his master and learn to obey it. As to himself, learning will do him no good, but a great deal of harm, making him disconsolate and unhappy. If you teach him how to read, he’ll want to know how to write, and this accomplished, he’ll be running away with himself. (Douglass, 2017, p. 14)

Mr. Auld’s fear did not stop Douglass from learning how to read. In fact, it only inspired him to become even more fearlessly determined to learn to read and write. For Douglass, Auld’s reaction was a “North Star” moment that led to education as a pathway to freedom. In his book, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave, Douglass spoke of this incident:

Whilst I was saddened by the thought of losing the aid of my kind mistress, I was gladdened by the invaluable instruction which, by the merest accident, I had gained from my master. Though conscious of the difficulty of learning without a teacher, I set out with high hope, and a fixed purpose, at whatever cost of trouble, to learn how to read. (Douglass, 2017, p. 15)

Even though his lessons with Mrs. Auld had ended, Douglass found creative ways to learn to read. I envision Douglass saying to himself, “If you don’t teach me to read directly, I will learn to read indirectly.” Douglass made friends with white children in the community that taught him to read in exchange for food. He learned how to write by watching ship carpenters write the names of ship parts on timbers in the shipyard. The poet Khalil Gibran beautifully describes this resilience when he says, “You may chain my hands, you may shackle my feet; you may even throw me into a dark prison; but you shall not enslave my thinking, because it is free!” Douglass, who became an abolitionist, outspoken orator, and author, made it his mission to obtain literacy by any means necessary.

Knowledge acquired by a slave was like a death knell to a slave owner. In order to destroy any semblance of humanity, plantation owners kept enslaved black people in the dark. The majority of enslaved people didn’t even know the year they were born or their lineage. It was a purposeful removal of identity in an effort to perpetuate the slave mentality. Several confederate states jointly imposed literacy restrictions on the enslaved using legislation that went beyond the shackling of bodies and extended into the shackling of minds. In their attempts to shackle our intellect, they failed to factor in the resilience of a people who endured centuries of brutal dehumanization and forced assimilation. A paradigm shift occurs in the thinking processes of enslaved people who gain knowledge. Their thinking moves from a slave mentality to a mentality of liberation, thus making them “unfit to be slaves,” as Frederick Douglass stated.

Alabama Anti-Literacy Laws and Jennie Proctor

The state of Alabama passed an anti-literacy law in the form of a slave code which states:

The Alabama Slave Code of 1833 included the following law “[S31] Any person who shall attempt to teach any free person of color, or slave, to spell, read or write, shall upon conviction thereof by indictment, be fined in a sum of not less than two hundred fifty dollars, nor more than five hundred dollars.”

Jennie Proctor was enslaved in the state of Alabama in 1850-1865. She did an interview with the Federal Writers’ Project in San Angelo Texas in 1937. The Federal Writers’ Project was a collection of interviews of over 2,300 formerly enslaved black people conducted in the 1930’s. In her interview, she gives a firsthand account of her life as a slave in Alabama. Jennie started working in the fields at the age of 10. In this interview, Jennie gives her account of learning how to read even though it was forbidden. She said,

“None of us wuz ’lowed to see a book or try to learn. Dey say we git smarter den dey wuz if we learn anythin’, but we slips around and gits hold of that Webster’s old blue back speller and we hides it ’til way in de night. Den we lights a little pine torch and studies dat spellin’ book. We learn it, too. I can read some now and write a little, too.”

Restrictions did not keep Jennie from learning how to read. In the wee hours of the night, she would use Webster’s old spelling book, lighting a pine torch to read the words. The black community knows how to make a way out of no way. Our role is that of a pathfinder, forced to come up with ways to get around the unjust limitations imposed on us by those who oppressed us. Despite being enslaved, Jennie refused to be defined or oppressed by her status. She was determined to learn how to read by any means necessary.

Georgia Anti-Literacy Laws and Mathilda Beasley

Anti-literacy laws were enacted in Georgia in 1829, which stated:

And be it further enacted, That if any slave, negro, or free person of colour, or any white person, shall teach any other slave, negro, or free person of colour, to read or write either written or printed characters, the said free person of colour or slave shall be punished by fine and whipping, or fine or whipping at the discretion of the court; and if a white person so offending, he, she, or they shall be punished with a fine, not exceeding five hundred dollars, and imprisonment in the common jail at the discretion of the court before whom said offender is tried.

Assented to, December 22, 1829 George R. Gilmer, Governor

Teaching people of color how to read was punishable by whippings, lashes, fines, and even death. However, black educators in Savannah, Georgia took profound risks to teach enslaved and free children of color how to read. Savannah is one of the oldest cities in Georgia. It is a picturesque place where oak trees are draped with Spanish moss, which provides shade from the hot Georgia sun. The Savannah River carries a cool breeze while residents enjoy sweet tea on the front porches of antebellum homes. One cannot imagine what slavery was like in this beautiful city centuries ago. The undercurrents of slavery have no respect for people or beautiful places. Slavery still operated concurrently with regular life. There’s a story of a courageous educator named Mathilda Beasley, who is practically unknown in the annals of black history. Mathilda was born in New Orleans and moved to Savannah, Georgia, in the 1850s. Despite the risks of fines and up to 32 lashes in the public square, Mathilda opened a “secret” school for enslaved and free children of color. Educating children of color in Savannah was Mathilda’s brave act against illiteracy and unjust laws. Mathilda’s bravery is noteworthy, but the students should also be recognized. The colored schools in Savannah were considered open secrets. Therefore, the students had to take extra precautions to hide from the authorities. To do this, they wrapped their books in newspapers, changed their school routes, and hid in a designated place if the authorities raided them. Both Mathilda and her students showed bravery, courage, and the willingness to learn by any means necessary.

Missouri Anti-Literacy Laws and John Berry Meachum

The state of Missouri, admitted as a slave state in 1821, passed an anti-literacy law in 1847 which states:

“No person shall keep or teach any school for the instruction of negroes or mulattoes, in reading or writing, in this State.”

In Missouri, this particular anti-literacy law targeted schools that taught black and mulatto students. Before this law was passed, schools had already been established for free and enslaved black people in the state. John Berry Meachum, a black man from Virginia, was instrumental in advancing the education of black people in Missouri. Meachum was a pastor, business owner, educator, and founder of the oldest black church in Missouri. He was born into slavery in Virginia. During his enslavement, Meachum learned the craft of carpentry. By the age of 21, he had earned enough money from carpentry to buy his freedom and the freedom of his father. Shortly after that, he bought his wife’s freedom after they both moved to St. Louis, Missouri. In 1825, Meachum was ordained as a Baptist minister and opened the First African Baptist Church in St. Louis. It also served as a school for free and enslaved residents of St. Louis. Close to 300 students were attending the school. As a religious leader, Meachum did not see education for children of color as a sacred duty, but rather as a means of preparing them for a future free from slavery. White residents of St. Louis began to view the education of free and enslaved people of color as a threat as slave revolt reports intensified. As a result, they introduced legislation banning education for all free and enslaved black people. Meachum was forced to close the school temporarily, but he did not allow the ordinance to deter him. He devised a plan to reopen the school through other means outside of the jurisdiction of the state. Using a steamboat on the Mississippi River, he established the Floating Freedom School. Meachum’s Freedom School continued to educate the enslaved and free people of color regardless of anti-literacy laws. By establishing a steamboat school in the face of unjust laws, Meachum demonstrated his willingness to educate black students by any means necessary.

Final Thoughts

It is said that “knowledge is power.” Historically, black people were deprived of knowledge due to anti-literacy laws. I believe anti-literacy is anti-knowledge. Although anti-literacy laws no longer exist, critical race theory (CRT) has emerged as a new form of this ideology. CRT examines how structural inequalities persist even though laws are in place to address them. However, lawmakers are participating in fear-mongering campaigns about critical race theory, claiming that it is being taught in the classrooms. These claims have no roots but are just the tentacles of falsehoods reaching into the hearts of those seeking to sanitize their bigotry. The manufactured version of CRT is just an attempt to justify the selective erasure of history that acknowledges the ugly truth of our nation’s past regarding people of color. Since CRT was introduced, twenty-two states have attempted or proposed legislation to regulate the teaching of racism in the classroom. Unfortunately, this has also resulted in the banning of books written by black authors. Laws are supposed to establish justice. Today, laws are being used as modern-day shackles of restriction reminiscent of the Jim Crow era, always separate and never equal. The mere fact that certain sectors of society would produce legislation to restrict another race of people is proof that they have proclaimed themselves as the prototype. This country must repent of historical misconceptions that one race is the prototype and that every culture must conform to it. It is impossible to live in a monochromatic world when it is filled with a kaleidoscope of beautiful people and cultures. You cannot escape diversity. It is everywhere and in everything. God created it that way. Learning about other cultures, whether from books or experiences, builds a sense of respect. A whitewashing or eradication of that knowledge would be detrimental to our society because you cannot respect what you do not understand. Whitewashing American history is futile. History is not black and white; history is in color. I believe the world would be a much better place if we began to view each other through the lens of humanity and deep respect for cultural diversity rather than through the lens of the color of our skin.

About Carliss Maddox

Carliss Maddox is a Maryland-based author, educator, and poet. She is the author of four children’s books and one novel. Her stories are inspired by personal experiences as an educator and life in general. Firstgarten, her first published children’s book, received a five-star review rating from Readers’ Favorite. You can connect with Carliss by visiting her website at https://www.carliandcompany.org/ or following Carliss on Instagram @carli_company.